Accelerator Success Metrics

Accelerators live and breathe startup metrics. They set the KPIs (key performance indicators — the most important metrics) that startups should report and try their best to teach them how to execute everything based on metrics. But how do accelerators fare on this themselves? How do they measure their success and report it to their stakeholders? What are the important accelerator metrics KPIs?

The status quo of accelerator metrics KPIs

Accelerators that track startup exits, funding, survival rates, and others, as part of their KPIs, depend on tracking startup progress after a program. Tracking and reporting are easy for those taking in small cohorts and offering them office space. They are in constant contact due to proximity. Consequently, not having a system in place is rarely an issue. Keeping track of five startups’ progress with spreadsheets works just fine. But it is not an efficient solution for accelerators working with larger cohorts or looking to scale up.

Accelerator KPIs should be closely related to the purpose of the accelerator

To choose the correct KPIs for an accelerator, you must go back to basics. You must remember why an accelerator exists in the first place, and bear in mind a very clear definition of success. But what is success?

For each accelerator, success has a different meaning. Because each has a unique reason for existing. Still, if you take a closer look at all accelerators, you discover they share several values or objectives. Let us look at some of the common ones:

- increase the number of startups or tech companies in the region;

- connect startups with corporations looking for innovation;

- change the local economic culture;

- help launch more companies founded by students;

- help with corporate or university marketing;

- drive innovation around a certain technology;

- access revenue for innovation in certain areas.

The reason an accelerator exists and its business model impact the way it selects and measures its KPIs. Some accelerators (in very rare cases) charge startups a fee, so they can have skin in the game, others take equity and depend directly on the success of the startup, and some rely on government funding to drive positive change. Naturally, they all report different accelerator metrics KPIs to their stakeholders.

Choosing relevant accelerator metrics KPIs

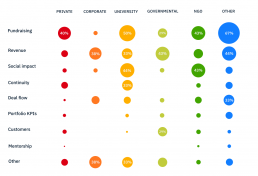

Metrics reported by accelerators usually depend on who their stakeholders are. University, private, corporate, NGO, and government programs have different types of metrics as their stakeholders look for different things in the data. As you can imagine, two accelerators will rarely end up using the same KPIs or reporting systems.

For private and corporate accelerators, success might mean revenue. If this is the case, relevant metrics could focus on how many startups achieved enough revenue to leave the accelerator. For a fair comparison, accelerators must know how fast the average startup reaches that revenue on its own. And how much faster this happens through the accelerator’s program.

For university and NGO accelerators, success might have a different meaning when it comes to success metrics. University accelerators might be interested in vanity numbers, like how many startups apply to their programs. While NGO accelerators might focus on the number of jobs created by startups.

The most common types of metrics tracked by accelerators are:

- Decision (immediate). They are used to drive decisions in key moments, especially when time is of the essence. Immediate metrics are there to maximize the output of the decision.

- Performance (lagging). They are used to inform and see how operations evolve, usually monthly, quarterly, or yearly. Lagging metrics help discover, understand, and predict future trends.

- Vanity. These metrics are the best looking ones. They are commonly used for PR purposes,

- Compliance. They are the ones that keep stakeholders satisfied. They often fall in the performance or vanity categories.

Findings

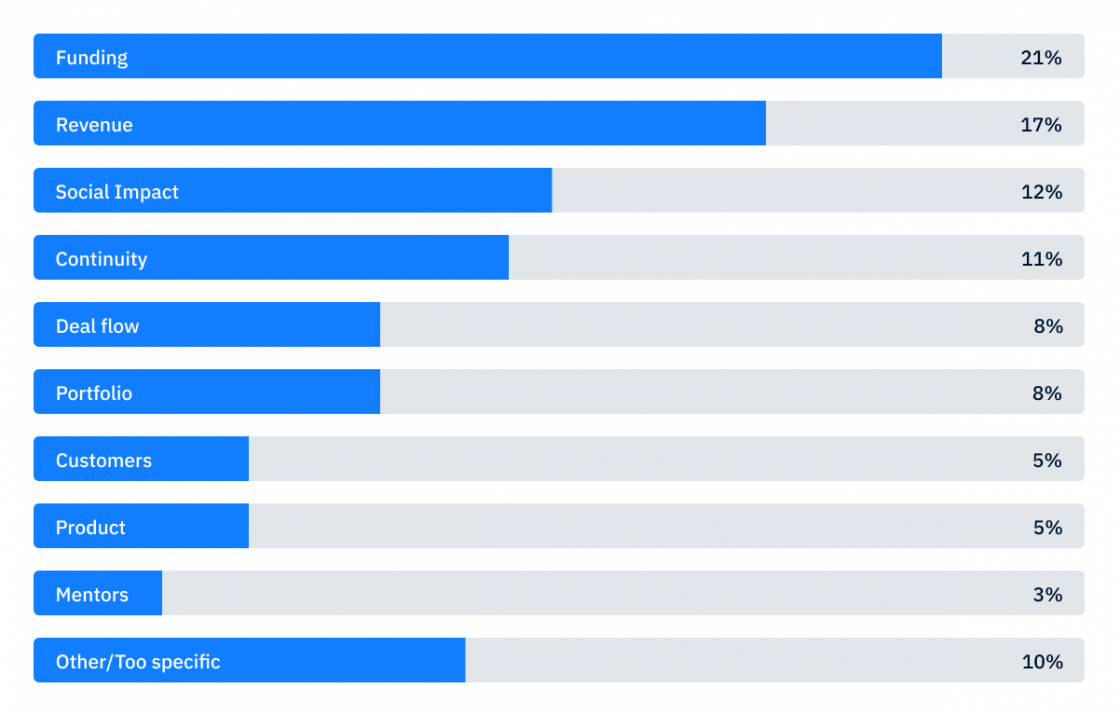

Our research shows that KPIs reported by accelerators are related more to startup performance than to accelerator performance. Perhaps accelerators should take a page from what they teach startups and take a harder look at their data. How do investments perform? What social impact does the program have? Also, if startups track user acquisition and performance KPIs, maybe accelerators should look at metrics related to their acquisition funnel, their performance, deal flow acquisition costs, etc.

The more an accelerator wants to scale, the more complex the data it tracks and reports will be. The old ways of tracking KPIs result solely in overhead and excessive spreadsheet usage. Change is imminent. Developing universal KPIs for accelerators can seem complicated due to their different purposes. But it is not mission impossible. It only requires perseverance, discipline, and the right tools.

Thoughts

- Starting an accelerator should be like starting any other business. It is all about defining a strategy (background, objectives, strategic approach, monitoring & KPIs). Accelerators that struggle with choosing success metrics (KPIs) should focus on three simple pillars: why, what and how. These pillars often trump complex management or strategy consulting frameworks, and they are a great way to ensure that all the stakeholders are aligned from the start, that the brand of the accelerator is built with consistency across all messages, and that everyone in the team works toward the same end goal. Watch Simon Sinek’s TED talk, which is a very inspiring way to think about clarifying your strategy.

- “Why” is the critical strategic part and the part that gets skipped most often, to get down to the tactical (“What”) and operational (“Why”). One aspect that should not be ignored is that an accelerator is often a startup organization with lots of assumptions, unknowns, and perils. Therefore, its success lies first and foremost in the “whys” of the accelerator champions (which can be its founders or key stakeholders). Here, strategy is about honesty. One thing is clear: being an accelerator manager is more often than not an underpaid job. People who take on this responsibility have different motivations. If these are not aligned with the ones of the other stakeholders, before being aligned with the accelerator’s “why”, the risk of internal conflict or inability to follow the strategy will be greater. Additionally, do not forget about the assets or competitive advantages the accelerator has at its disposal (capital, know-how, relationships, ecosystem, etc).

- “What” takes into account the broad lines of the tactical approach. This will define the format (accelerator, incubator, fund), focus (education, knowledge transfer, impact, growth, fundraising) and resources needed. Accelerators should also be honest about how they measure reaching their goals and why they need to look at their data. This “why” should carry infinitely more weight than the pleasure of measuring.

- “How” gets into more detail about decisions and actionability, and details the actions and planning to reach the objectives from the previous point. If the previous two are flawed, the chances of these actions leading to excellent results (but not the right outcomes) increase.

- The old ways of tracking accelerator metrics KPIs in spreadsheets will not work forever. If accelerators want to scale up or become more efficient, a system (other than spreadsheets and forms) is essential, as a lot of accelerators measuring success is linked to getting the KPIs of each company. As we discovered, this is a huge challenge for more than 42% of accelerators.

Conclusion

Running an accelerator is no easy job. On the one hand, startups are high maintenance. You have to manage expectations and potential conflicts with startup founders, you have to create an environment where they thrive and make sure they get all the resources they need to achieve success. In addition, getting startups to track and report their metrics is a tough job. On the other hand, you have to manage the expectations and demands of your stakeholders, regardless of accelerator type. Surely simplifying the one part you can actually control (your own KPIs) will have a positive impact on your accelerator.

University Accelerators

Universities that have embraced entrepreneurship and innovation as part of their curriculum are a good starting point for the entrepreneurial journey of the youth. Their first role when running an accelerator program is to convince students of the viability of entrepreneurship as a career path. But that should not stop there. University accelerators should be viewed as the safest place in which future entrepreneurs can practice real-world skills. They are the only places where it is alright to fail, as consequences are minimal.

A university accelerator is a controlled sandbox where future startups can train for their future success and challenges. A lot of successful startup stories don’t come from first-time founders. Which is why being able to build their first startup early on, will give students a well-needed experience in this field.

Findings and insights

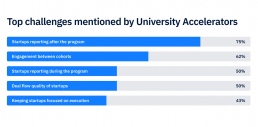

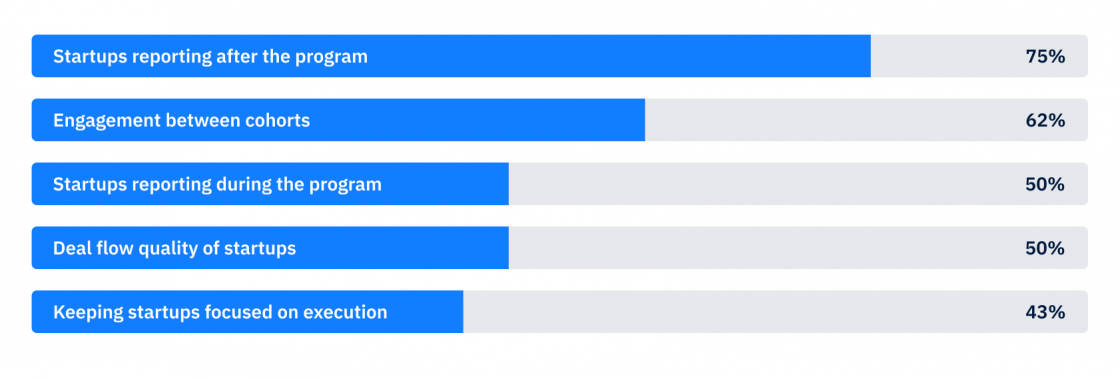

- Most university accelerators struggle with startup reporting after the program. Our study shows that about 75% of university accelerators come up against this challenge. A reason for this could be the lack of a good reporting system to compile, analyze, and share data. Clarity is absent. In consequence, the participants fail to see the real value of university accelerator data, which could potentially help them transform a summer project into a first time successful startup.

- Startups reporting during the program is almost as challenging as reporting after the program. Unified and constant data is crucial to the success of an accelerator. Without this data, it can be hard for them to be taken seriously by students and future entrepreneurs, as well as by investors.

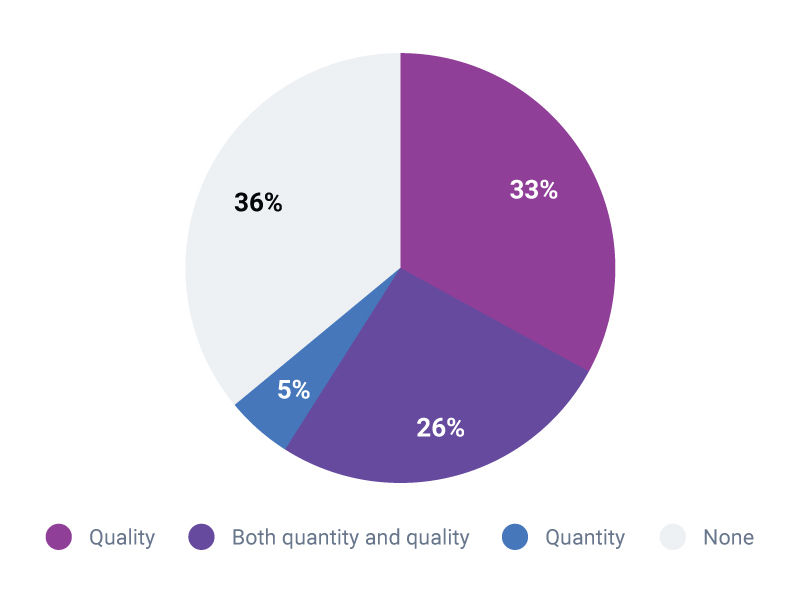

- One might argue that part of the challenges that university accelerators have with deal flow quality could be due to a lack of focus. 2 out of 3 accelerators have a generic target and draw a large variety of startups. But quantity is never equal to quality. One way of attracting the right kind of startups could be having a narrow focus, vertically or horizontally, or both. Our study shows that 50% of university accelerators have a problem finding quality leads, while only 27% say they have a problem with quantity (mostly due to increasing competition in the market).

- There is an unfortunate idea among students that university accelerators are an opportunity to learn rather than anything else. While being a great exercise for the future, university accelerators could be the launchpad for some truly successful startups. If only students would remain loyal to them and put in the work.

“Getting students to commit to an accelerator when they have other opportunities available to them during the summer”

— Jerry Ciolino, Startup UCLA

- The majority of university accelerators offer perks. 80% offer office space as well as legal & accounting support. These are golden for a startup. Legal and accounting are two pressure points where costly mistakes are often made. If we combine these perks with the early-stage access to hard data, networking, access to labs, coaching, technical services, and other resources, we conclude that university accelerators are an important pillar sustaining the growth of entrepreneurs.

- The alumni and mentor’s networks are two reasons for which university accelerators should be viewed as serious opportunities for future entrepreneurs. More than 60% of university accelerators introduce startups to their potential clients.

Thoughts

- If universities could show students the potential of their accelerator programs through hard data, perhaps students would treat these programs with a higher level of dedication. Which will, in turn, attract better applications and ultimately better investors.

- University accelerators could choose to narrow their focus based on their assets: mentors, alumni, and their ability to attract a certain talent.

- Having a sandbox to practice and to make all possible mistakes with little consequence is a unique opportunity for students. And the data that results from this sandbox could give investors a better idea about where the startup world is headed in the future.

Until recently, young entrepreneurs had to choose between getting an education and starting their business. Now, as a student, you have a higher chance of launching a successful startup inside a university accelerator. Thankfully, entrepreneurship has become a study subject in itself and university accelerators offer students the opportunity to practice what they are taught. In fact, university accelerators can be thought of as sandboxes for future startups.

Corporate Accelerators

The different mentalities that startup and corporate entities possess make them an unusual match. There are over 200 corporate accelerators looking to make a difference in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, but their efforts are most often seen as PR stunts. They have the infrastructure and market capital needed to run these types of programs but fail to resonate with what startups are at their core.

Findings and insights

- Many corporate accelerators start as a PR or CSR program, either pushed by an internal champion with access to the CEO and board, or by copying competitors’ initiative. In many situations, these are a waste of resources. However, we’ve seen situations where corporate accelerators have filled a gap and have ignited an ecosystem. In Thailand, for example, corporate accelerators are in fact the ones that are pushing this industry further, with corporate VC being the driving force behind.

- There is a misguided mindset among many founders, that corporates are dying dinosaurs, ripe for disruption. The story of David and Goliath is very appealing, but it rarely occurs in real life. The right mindset is a win-win partnership, where a startup brings innovative ideas, an unreplicable speed of execution and iteration, scrappiness, and a corporate brings resources, domain knowledge, and access to customers with a low CAC.

- That being said, implementing an early-stage startup product in an enterprise environment is rarely feasible because of compliance, risk, long decision cycles and more. This is an extra reason to carefully choose success KPIs on both sides, with realistic expectations (check whether the corporate partner has ever done such implementations before).

- While private accelerators struggle with funding, corporate accelerators struggle with internal politics. A corporation is usually too slow and bureaucratic to put together successful programs. Corporations that run global and cross-industrial accelerator programs have united forces with other already known accelerators, taking advantage of the know-how they can bring to the table. The way corporate accelerators have evolved is either with in-house programs (Wayra and Microsoft Ventures), outsourced programs (Barclays, Kaplan, and Disney) or operated in partnerships (Citrix and Red Hat).

- We have recently seen the opposite phenomenon: corporations withdrawing from partnerships with private accelerators, and (re)starting their programs on their own. We don’t have any data to evaluate the outcomes of these initiatives, so we are waiting to see results, despite being a bit pessimistic.

“Our Job Is to Empower and Make Ourselves Not Required”: A Conversation With Catapult’s Mike Boorn Plener

Mike Boorn Plener is a catalyst for change in people and organizations, finding value nobody else sees. He has built several successful software-related businesses, worked on large consumer databases and spent time in corporate. Today, Mike helps entrepreneurs grow their businesses rapidly and raise capital through a highly curated approach to accelerated business growth. Mike gained an MSc at the Technical University of Denmark and a BCom at Copenhagen Business School. He is passionate about business, food, travel, and family. He regularly speaks, judges and moderates panels on stage. His first speaking engagement was at 27 in front of 300+ people in Helsinki.

Catapult, one of the companies he has founded, helps entrepreneurs and business owners build revenue in the field with the founder, set up systems and processes, establish a board and raise capital.

Why did you choose the accelerator business model and not a venture builder, seed fund, angel group etc?

The biggest problem that founders have is scaling their business. The scaling of the revenue, the understanding of revenue modeling, the implementation of marketing models—these are indicators that mean they can do things in a scale fashion. There are a few related issues, but at the early stages of scaling, the problem is getting the revenue off the ground. If you haven’t got revenue, nothing else much works.

After startups start getting revenue, they need to expand their team, which can be very tricky. Most people have only hired in one specific niche and now they have to hire broadly and add to their team a salesperson, a financial administrator, a software developer, etc. And one thing that might be an important character trait for a software developer is definitely not the same character trait that you want in a successful salesperson.

The creation of systems isn’t an afterthought, because having structures, systems, processes, and procedures in place is what makes you scalable.

Once they get over the hurdle of hiring, management structure falls apart because they didn't have any systems, they didn’t have any process, they didn’t have any procedures. What these young businesses fail to understand is that the reason these big businesses got big was because they were forced to create structures and systems that allowed them to scale. The creation of systems isn’t an afterthought, because having structures, systems, processes, and procedures in place is what makes you scalable.

If we choose to set up a venture capital fund or something similar, we are only addressing the money issue. The choice of the business model of an accelerator is because, within the framework of being an accelerator, we can resolve all of those things.

There are a lot of accelerators and incubators that have a “spray and pray” approach, taking as many companies at early-stage and accelerating them for three months, but I understand that your model is pretty different. Can you expand on that?

We go through a very thorough and broad selection process. We evaluated over 1,000 companies in the last year, and from that, we find 50 or 100 that have some value, and from that hundred, there's probably 25 to 35 typically that really impress us. The significant impact is created not by helping everybody come a little bit longer but is created by helping the few that really have a promise to come a long way.

It's those that come a long way, that are going to go on and hire 100 people, impact the economy, and export whatever they did out of Australia. This is a model that's based on the mathematics of what actually works, not a commentary on social justice or lack of justice. Where can we actually, with the least amount of resources, have the greatest amount of impact? That's what we designed for.

How does your model radically differentiate from the standard accelerator model?

The thing that is unique about our model is that we do not help startups for three months and then kick them out the other end and see what happens. We would rather take fewer, but be able to support them for as long as that may take because it’s a treacherous path they’re going on.

Other models that we’ve looked at, take in startups for a couple of months and at the end of the program, the startups get dumped and don’t know what to do next. Startups get smothered with experts and mentors, and typically those mentors have five different opinions on an afternoon which confuses them. And once the program ends, the startups don’t know where to go, and all the support network is not really there because the mentors are busy with the next cohort.

Stay up to date!

Every few weeks, we send out a curated newsletter with articles and insights from top accelerators and investors.

By signing up you agree with our terms and privacy policy.

Even though it doesn’t happen overnight, everyone is on a quest to find success. In your experience, how do startups get there, what determines success?

There's a couple of fundamental things that we've realized. First of all, advisors are lovely but it's even better to have skin in the game. There's nothing wrong with having mentors and advisors and some of them are bloody brilliant, but it's even better if those same people have some kind of skin in the game, whether they have shares or future options or whatever it might be. It creates a culture where they have just that little bit more incentive to make sure it works.

Some of the startups have complained that they’ve seen five mentors across five hours and each of them had five different opinions on what they are supposed to do. Which leaves them scared and clueless on how to proceed. That's the typical model that has been pushed out there for decades. You’ll engage so-called industry veterans and they’ll come in as free mentors and they’ll give you their opinion. And there's nothing wrong with opinions, but at the end of the day, it’s the action and the execution of those opinions that matter.

There is not even 100 things that can actually guarantee you success. However, we found about 120 or so things that if they're not executed successfully they guarantee failure.

The other big thing we've seen is that over the years people have been on stages saying “Do this one thing and you will be successful, just like I was”. If there was just one thing we would all be multi-billionaires because we would all know what that one thing is and we'll just go and do it. It doesn't work like that. Before I started Catapult one of the things I asked myself was what if there isn’t just one thing, but one hundred things that will determine success. And the finding was kind of pessimistic. There are not even 100 things that can actually guarantee you success. However, we found about 120 or so things that if they're not executed successfully they guarantee failure.

Can you give us some examples of the most common ones?

For example, solo founders have a lesser chance of being successful compared to two founders or three. But if you get to four founders, then it starts going backward again. However, some things are far more concrete and a lot of founders don’t even think about them. We deal with businesses every week that haven't got a shareholders agreement. And the reality is that just like in marriages, tempers flare and they can split up. If they don’t have a contract, because they don’t want to spend $3,000 for the lawyers, they end up spending $3 million blowing up a business.

That is just an example of the 120 factors. These are ordinary housekeeping things that intelligent people, would be going “yeah, of course, we do that”. A very simplistic example is to know you require having a job description when hiring. That sounds like such a daft thing, lacking importance. What if you don't have one? They do become very important. So it's all of those little things that you could easily tick off a list.

Having 120 things to check, besides trying to get to revenue and keep the startup afloat can be very tricky. What do startups most often get wrong in the process?

We see a lot of businesses that we connect with slightly earlier than we would like to take them in. There is a step of product-market fit. They have the idea, they spoke to 25 of their friends and everybody thought that was lovely. They went ahead to develop the products. They develop the website and then they push the go button and are now trying to get clients. But the clients have all sorts of requests, they want it in different colors, different sizes or need different functionalities. And the product creators wish they thought about that before they developed it because they only have the production model that can’t be changed. That is because so many startups think they know what the world wants.

It is more important to have a genius marketing model and an amazing commercial evolution than to have a perfect product

You have to go and ask people before you start developing. The first part of development is a PDF file that just describes what it is you're trying to do and afterward have 100 coffee meetings. If during those 100 coffee meetings roughly 50 of them found the idea interesting and useful, you go ahead and build a prototype. Afterward, you go and show that to the same hundred people. Now if there are still 30 or 40 of them that are willing to buy it, then you know you’ve got something, and it's time to go back in the lab and actually build one for real so that you can replicate it and build 100,000 of them.

It is more important to have a genius marketing model and an amazing commercial evolution than to have a perfect product. The product can always be improved, but if you have a flawed commercial model you will run out of money.

It tends to be one of the two: either get the product right but get the business model wrong or they get the business model right but they just don't land with the product and the product-market fit is just not there.

What about once startups get into your accelerator program. What did you find out that works, based on what you do to help them with?

There are three things that we help with that have the biggest impact: the revenue, the funding, and the people.

Before anything else, people need to spend some time creating an attractive brand and hold themselves accountable to do what they say they’re going to do. This is not new science, it has been around for decades. It’s a lot easier to sell something that has a very attractive brand than it is to sell something that does not. Attractiveness is not necessarily about the shape of the coke bottle or the smile of a girl, but it's about whether or not it is fully aligned with the values of the future consumer. We need precise models of understanding what the consumers think, what they know, what they smell, who they listen to, what their influences are.

The second thing is related to revenue. In terms of their revenue models, we find that most people have a linear or singular revenue model. They think that if they go to Google and buy 100 clicks, they’ll get five signups and from five signups they'll get one purchase. We give them a database of 2 million potential consumers because we don't want anyone that we're working with to pay for advertising. It's strictly prohibited.

I can't make investors love them, that's their job. We can get the horses to the water but we can't force them to drink it.

The third category that we deal with in a practical sense is helping with people-problems. We help them with psych tests, personality tests and more. But we also help if there are two, maybe three co-founders, by creating a platform of shared beliefs and values. We always ask them what they love to do and require them to forget about thinking and start feeling. We bring everything away from the “doing realm” and into the “being realm”. Because all of us have magical superpowers when we are in the being realm, none of us have magical superpowers when we are in the doing realm. There are only 24 hours and we can only check so many items on the to-do list, we can only tap so fast on the keyboard.

In addition, is again, the capital side. A very practical message that we say to people is that I can't get an investor for them, because investors have to like them and their business, they are not going to invest in me. What I can do is I can make sure that their due diligence is squeaky clean. What I can do is to make sure that their financial model will stand up to any level of scrutiny for even the worst analyst. But I can't make investors love them, that's their job. We can get the horses to the water but we can't force them to drink it.

These are the key areas where we can make a lot of difference. One important aspect to note is that we're not here to do the work for them. We're not the founder, we don't have a 51% interest in the business, so our job is actually to empower them and make ourselves not required. I don't want to create dependency.

How much time on average do you spend on each company?

Somewhere between 100 to 200 hours across, roughly, a six month period. The intensive period for us is typically the first three to six months. Within the first three or six months, we will spend 150 hours on each individual client, because there is a lot of stuff and some of that is done one-on-one, which is obviously very expensive and some of it is done one-too-many, as in the group sessions or seminars.

How big is your team, who are the people that are involved with the startups?

We have a couple of different layers. We have an inner team, which is basically management, sales, and marketing, and then we have, what we refer to, super coaches. The super coaches are comprised of four different people or more in any given month just because we want to draw different skills. We get people with the proper expertise to consult depending on the type of business the startup is in. And the third layer is made out of service providers, which is something that is delivered as a freebie to startups, as part of the package.

A lot of people look at this like it’s an art instead of science. What's the role of data and reporting and tracking of that data versus just gut feeling in the whole process?

We always lead with the gut, but always back it up with data. We don't go on whims and work with people that we love, but if I don't have a good feeling about a business or about a founder in the first place that doesn’t help either. We have a “don’t work with assholes” policy. However, if we do get a good feeling about the founder, the business, the market they’re in, and they've even talked to some of their customers and got lots of feedback, we look further into the data.

It’s important to track data. You want to monitor the performance of any scaling business. The moment you start hitting revenue you want to monitor it, you want to monitor COG, you want to monitor CAC, you want to monitor ROI. And you want to monitor a lot more frequently than most people do. I'm a big believer in monitoring either daily or weekly. If it's an online business, I want to see daily stats, nothing less. If it's not an online business, I'm happy with weekly stats, but I don't want to see a monthly or quarterly report. When you speak to someone that runs a hospitality venue, they will count the money twice a day, because if they have poor revenue in the morning, they're going to figure something out to make up the lost revenue in the afternoon. What a lot of people don’t understand is that you can’t make today’s revenue, tomorrow. No one’s invented that time machine.

From your point of view, what would be the advice that you would have for other accelerators popping up so they don't make mistakes for 3-5 years before they finally learn something?

They need to go with whatever feels right. What's really important is that they stop for a moment and think about a model that underpins what they do because having a model is actually what we are asking the businesses that we're supporting to have. I see too many accelerators or incubators that try to do what everybody else is doing. It could be that everybody else is right but there's nothing wrong with having a little bit of creativity and developing your own model and say what you stand for and what you believe in. As we progress over the next five or ten years there's going to be a lot more accelerators and incubators then we have today because we're still only at the very early cusp of this industry. The more you can stand apart from everybody else, the better.

Keen to collaborate? Catapult would love to hear from you! Send us your details here and we’ll touch base with you:

Private Accelerators

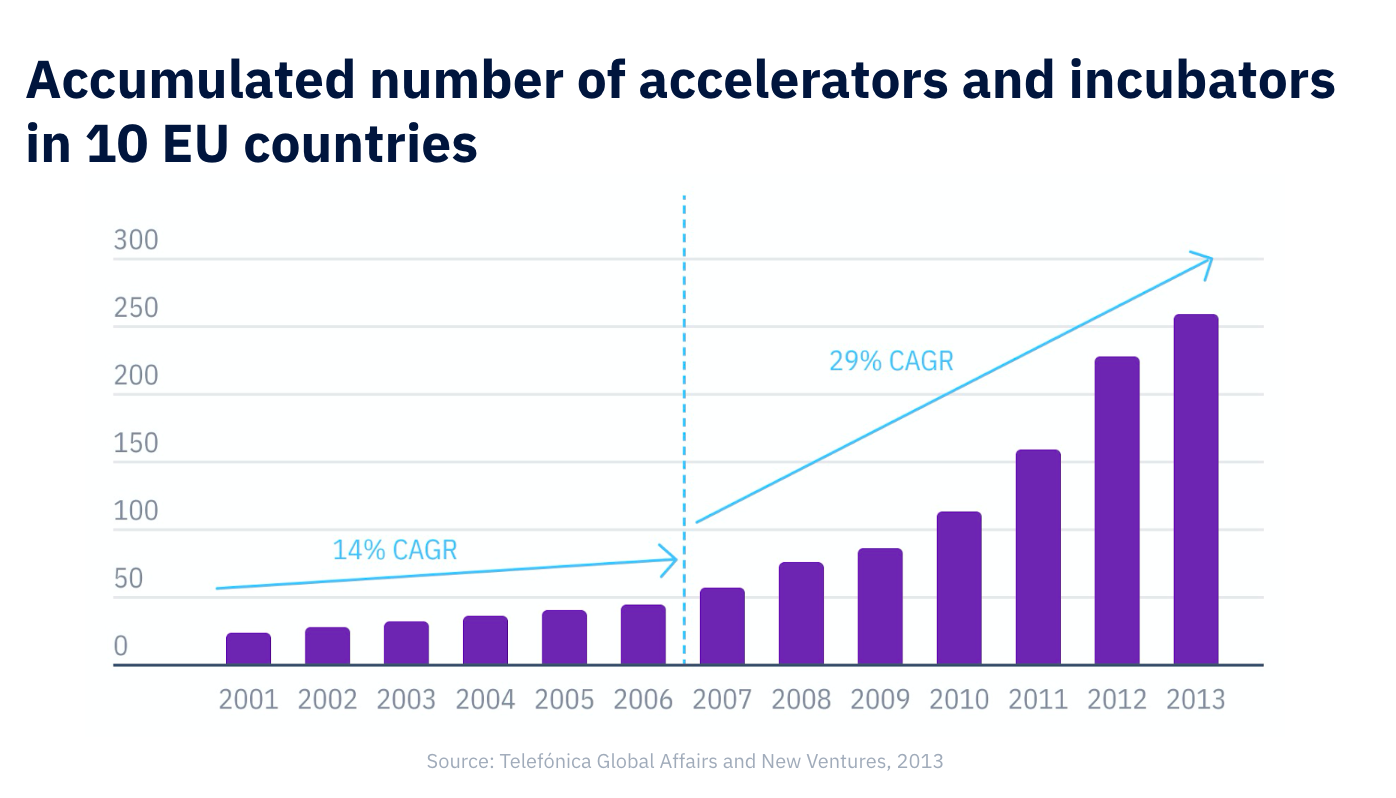

Ever since Y Combinator launched in 2005 in Cambridge, the contagious enthusiasm of accelerating startups has spread across the world. In 2016, Gust reported more than 10,000 accelerators worldwide, and a Telefonica study put the growth of the industry at 30% CAGR.

We’ve seen quite a few situations of new accelerators popping up, copying the YCombinator or TechStars model and expecting that hope (or “spray and pray”, how it’s often called in the investment world) will lead to success. In most cases, within three years, most of these ventures turned into a proper seed fund, an educational program, a corporate marketing initiative, or they just died (unfortunately, there is no clear data of this—maybe we’ll look at it in a further study).

We’ve seen quite a few situations of new accelerators popping up, copying the YCombinator or TechStars model and expecting that hope (or “spray and pray”, how it’s often called in the investment world) will lead to success. In most cases, within three years, most of these ventures turned into a proper seed fund, an educational program, a corporate marketing initiative, or they just died (unfortunately, there is no clear data of this—maybe we’ll look at it in a further study).

“Accelerators are charities, not businesses”

—Jon Bradford, F6S Cofounder, former TechStars London managing director

Jon further argues that it’s hard to employ experienced managers in accelerators (most of the good ones would be better off being a startup founder, or in a corporate job). On top of this, the risk is huge, the equity percentages low, and the return-on-investment is low. Essentially, most accelerators fail to capture the value they are creating.

One of the main reasons is the lack of a set of best-practices for any situation. We’ve tried to compile some of them, but the hard reality is that there are few things that work universally. We’ve found out more bad-practices, such as copying existing models (YC, TechStars, or other successful accelerators), without considering the foundation of any accelerator:

- Talent & know-how (local strong education).

- Industry and business (purchasing power, strategic partnerships)

- Capital (public and private sources)

- Strong networks (personal or professional)

- Culture (risk-aversion, collaboration, innovation, trust etc.)

What private accelerators often forget is that they are startups themselves—startups helping other startups. They have limited resources, tons of assumptions, a business model and approach yet to be validated, and very slim chances to turn into a sustainable, high-growth business.

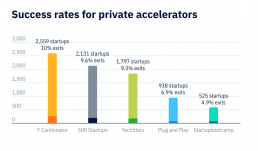

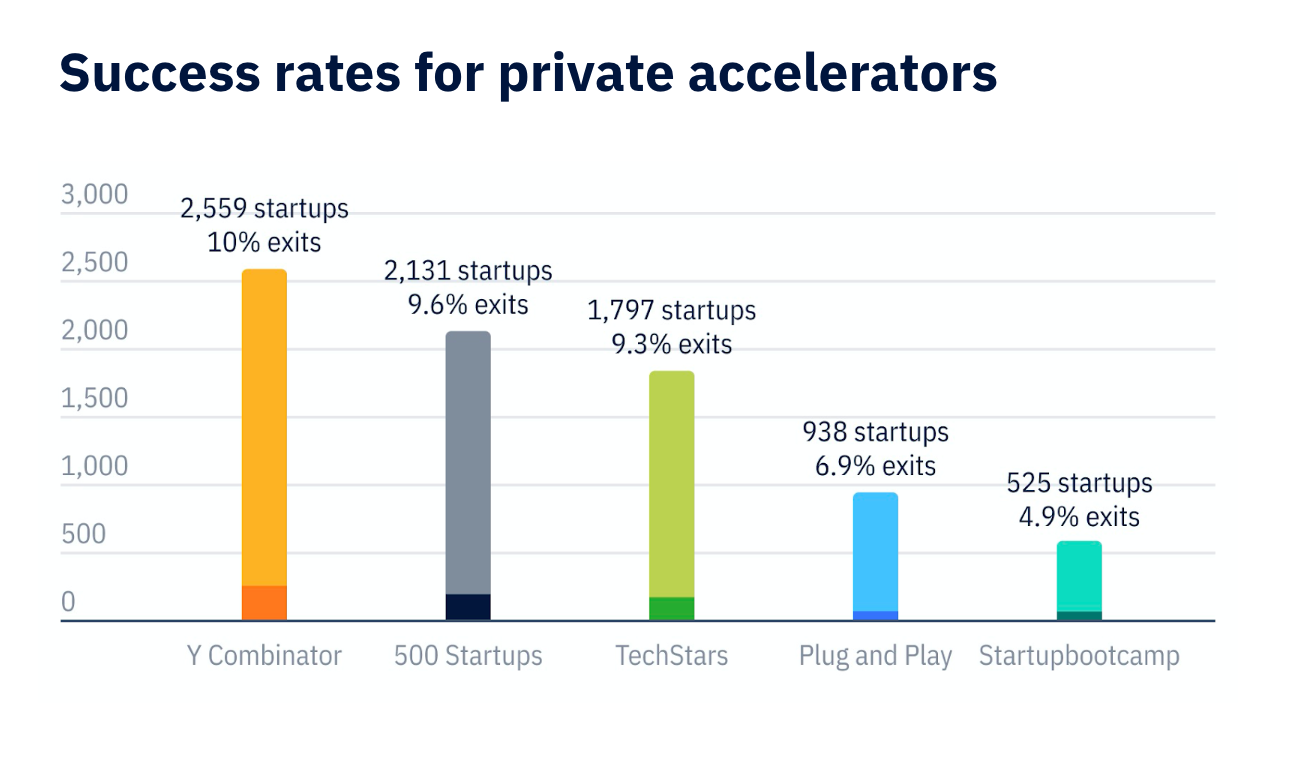

As a standalone, independent business, a private accelerator has very few chances to stay alive beyond 2-3 years. Even the largest accelerators have low success rates:

- Y Combinator invested in 2,559 startups, of which 260 exited (10%).

- 500 Startups invested in 2,131startups, of which 206 exited (9.6%).

- TechStars invested in 1,797 startups, of which 168 exited (9.3%).

- Plug and Play invested in 938 startups, of which 65 exited (6.9%)

- Startupbootcamp invested in 525 startups, of which 26 exited (4.9%).

These are some of the strategies employed by private accelerators:

- Function as a scouting & de-risking program for pre-seed or seed-stage investments of a seed fund or micro VC.

- Fund operations from other sources (corporate partnerships, educational programs, governmental grants or public funds).

- Create a very strong network for follow-on investments.

- Function as a fund (as strategy, success metrics), but with a high-touch approach for new investments; usually this means no cohorts.

- Charge for participation, instead of taking equity.

Failure can be avoided and, while few accelerators can become successful, building sustainability is possible by choosing the right business model (or transition to the right business model) from the start of the process. It’s a long journey and, most likely, this will be a topic for further research.

Mentoring Beyond Bragging Rights and Looking Good

This is part five from a series of insights drawn from 50 in-depth interviews taken over the past two years and 126 responses to a survey we sent out recently. To better understand our process and the methodology behind these findings, make sure to read Disciplined Accelerator: Introduction.

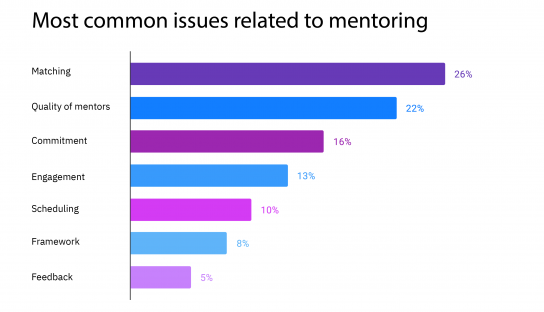

Most programs face issues with mentoring—from finding the right mentors, keeping them engaged, matching mentors with startups, to getting feedback and improving the mentoring program.

Findings

Findings

- Matching mentors with startups is a tedious process for various reasons. Many startups chase famous/known mentors, who have less availability, while disregarding less popular mentors who might be more willing to give time and help. Matching mentors with startups in the beginning is not a guarantee of effective mentoring throughout the program.

- A lot of programs present an impressive mentor pool to startups, however more than 70% of the mentors fail to deliver on the initial expectations. Lack of commitment and engagement is a frequent problem and few accelerators have managed to find the right incentives. Some accelerators rely on paid mentors (whom should rather be called “consultants”), an approach that results into better retention of mentors but is hardly affordable for most programs.

- Remote mentoring sessions are harder to schedule and keep track of (mostly because of mentor commitment/engagement decreasing after the start of the program). On-site, face-to-face sessions are more effective usually, as mentor can dedicate a longer period to mentor 2-3 startup teams.

Insights

- Motivation and behavior is radically changed by including any external incentives (money, equity). Each approach needs a different mentor selection, onboarding, and managing process. “Free” mentoring often means low commitment and the solution is counter-intuitive: ask mentors for more. By getting them involved in scouting, reviewing applications, onboarding, evaluation sessions, demo days, and other activities will increase their motivation and engagement.

- Build a diverse mentor pool by including several categories: industry executives have an increasing interest in the startup world, the energy and grind being different from their regular workplace, and can be a source of great connections and customers; successful entrepreneurs and alumni who have already gone through the program and had their startups funded are happy to share their unique experiences and viewpoints; investors have an ongoing interest in your startups and will provide healthy and candid advice, while keeping them engaged might result in easier follow-on financing and support; accelerator staff might know a lot about what startups go through, especially in the early stages.

“We get some of our best coaches/mentors from BigCo execs leaving their corporate jobs and who want to get into the startup space.”

— Jackie Willmot, XLerateHealth

- Onboarding and training the mentors is often overlooked. One of our survey respondents, Accelerace (Denmark) has been referenced many times for having one of the best training programs for mentors. Introduce your mentors to all the steps in the program, the people involved, the deadlines, the schedules. Brief them in advance on the stage of each startup entering the program. Train them on how to be better teachers. Some mentors may know the business side of things but lack skills in teaching forward their knowledge. They know science, and data, and metrics but often encounter issues in dealing with the entrepreneurs at an emotional level so understanding also the different aspects in startups vs corporates (Lean Startup approach, validating experiments and assumptions, dealing with uncertainty and chaos etc.).

- Keep your mentor accountable by signing a commitment agreement when you onboard them (similar to a volunteering agreement). It might seem too much to ask busy people to do this, but if they won’t do it how can you expect them to deliver on their promises? Another thing is to separate your pool into “mentors” (the ones who are truly committed and deliver on their promises), “experts” (the ones who will help once or twice in a while, but won’t commit to get involved recurrently), and “contacts” (the ones whom might not be committed or engaged but still be a useful connection). Ask your engaged mentors to bring other people in their network as mentors, as long as they are involved in their onboarding and engagement—this way you will be able to create a strong support team for your programs. In the end, it’s nothing different than a volunteering program for successful, busy people.

Education Is Essential for Incubation but Disruptive for Acceleration

This is part four from a series of insights drawn from 50 in-depth interviews taken over the past two years and 126 responses to a survey we sent out recently. To better understand our process and the methodology behind these findings, make sure to read Disciplined Accelerator: Introduction.

Before sharing the findings, I’d like to clarify the classification system that we use when it comes to startup programs. The market uses acceleration, incubation, and other terms in a very inconsistent way (it seems everyone has a different understanding of what the terms mean).

We aim to establish a consistent naming system based on semantic consideration first (incubation means to bring something to hatching, while acceleration means to increase the speed of an already moving object).

- Pre-incubation: Applies to founders/teams with an intention to start a business or a rough idea. The process consists mostly in education and primary market research (customer discovery). The end goal is to get to a complete & researched business plan, canvas or pitch deck.

- Incubation: Applies to teams with an initial business understanding (not just an idea). The process involves education, customer discovery, mentoring and solution development. The end goal is to launch an MVBP (a minimum viable business product — that helps prove business assumptions, not product usage assumptions).

- Acceleration: Applies to teams with an MVP or even initial customers. The acceleration process should include minimal education, and be a more customized approach to help teams to get from initial revenue to predictable/recurring revenue. From our experience, education in this stage is defocusing founders from having clear goals.

- Growth: Applies to teams with recurring revenue and modest growth. The process should be focused on sales, marketing, mentoring and support, the end goal being increasing growth and retention metrics.

Some programs may include more phases, but in our experience, building a successful business takes at least 3 months per each stage (especially considering that in the pre-incubation phase many founders have other commitments or jobs preventing them from being available 100% of their time).

Findings

- Each accelerator has different requirements when selecting candidates and startups are at different stages of maturity when they enter the program. Applying the same curricula to all of them is not efficient but seems to be the ‘default’ approach because ‘everyone is doing it’.

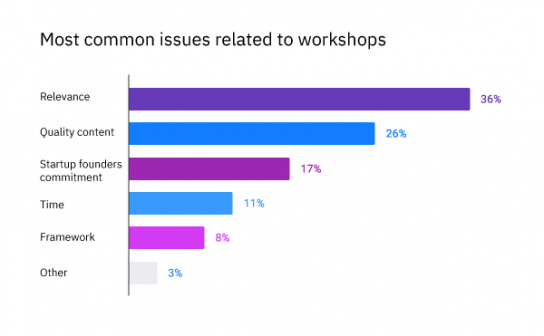

- Founders lack interest and don’t pay attention if they participate in a workshop that does not fit their current needs. They come to see this part of the program not as an opportunity to learn and grow, but as a tiny box they need to mark done in their quest for funding.

- The topics approached are not often relevant to both the stage the startup is in, and the people participating in the workshop, their experience and specific needs in each journey. The less homogenous a program cohort is, the more difficult is for the curricula to be helpful and relevant to the teams. Earlier stages (pre-incubation programs) can fit a curricula easier than later stage (acceleration or growth programs).

- Some workshops defocus teams from focusing on the end goal, as they jump to the opportunity of applying in practice what they learn, despite not being strategic.

Thoughts

Thoughts

- Pre-incubation programs should have 50-75% educational content (the rest being dedicated to research). Mentoring is not very useful at this stage (unless mentors are the educators).

- Incubation programs should not have more than 50% education, to allow time for experimenting, testing assumptions and ‘getting out of the building’. Too much education will distract teams from connecting with customers. True useful knowledge in such programs is found in customer conversations, not workshops.

- Acceleration should not be an educational program ending with a Demo Day, but a process aimed at helping build successful businesses by offering the right support. Build your acceleration process to help you reach your end goals, considering the available resources. In any case, education should come in the form of mentoring and customized support to help each startup on their journey.

- Consider creating a library with curated educational resources (and experts at hand) that will be accessible to your teams and be a reference point in case of need.

- Don’t forget to educate your mentors. Some of them have different views on building businesses (especially those who work in larger corporations), which can result in conflicting or hard-to-implement advice in a startup. At least an introduction to Lean Startup, Business Model Canvas, and Disciplined Entrepreneurship is recommended.

Lack of Reporting Discipline Is Most Often the Accelerator’s Fault

This is part three from a series of insights drawn from 50 in-depth interviews taken over the past two years and 126 responses to a survey we sent out recently. The focus is startup reporting: challenges and insights.To better understand our process and the methodology behind these findings, make sure to read Disciplined Accelerator: Introduction.

Findings on challenges startups and accelerators have with reporting

- Collecting data from startups takes up a lot of time and energy. There are no proper incentives that are strong enough to keep founders from moving on to their next stages of their startup journey, leaving accelerators stranded.

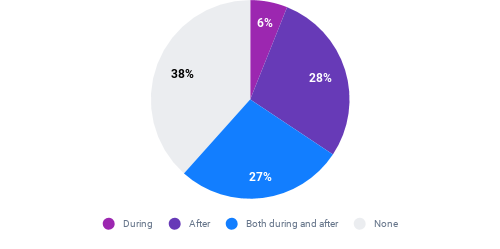

- 42% of all accelerators struggle with startup reporting. 30% face this issue mostly after the program ends. 28% deal with it both during and after the program.

- There is a strong connection between the number of startups each accelerator takes per program and the number of accelerators mentioned reporting as a main challenge. Half of the accelerators which accept fewer than 20 startups/program have mentioned no problem with reporting, while 60% of accelerators that take in from 30 to over 100 startups/program mentioned having this issue.

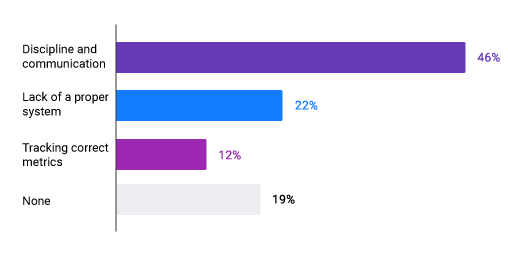

- Startup reporting issues are considered to be caused by lack of a proper system to collect metrics, knowing the correct metrics to track for each type of startup based on their business model and the stage they are at, and a lack of discipline from founders that fail to comply with this request.

Thoughts

Thoughts

- Most founders are talented business or technical professionals, but lack of skill is not among the top causes of startup failure. Execution capabilities are, and most often these are caused by the lack of internal accountability processes and systems. The role of an accelerator is also to help a startup get better at execution. Reporting is an essential part of accountability (not only external—to the accelerator), but also internal (between team members).

- Therefore, reporting discipline should start during the acceleration/incubation program and should be enforced through the acceleration contract/agreement. Regardless of whether the accelerator has invested cash in the company, reporting should be treated as a main priority in building execution excellence.

“Startups are so focused on the next challenge, reporting metrics falls behind on the priority list.”

— Matthew Forman, Portland State Business Accelerator

- Accountability should be first understood, then enforced. Startup reporting is a form of reflection/focus that is essential in building a healthy, functional company. Lack of reflection, focus or prioritization does not only cause potential issues between startup and accelerator/investors but also within the founding or extended team. This symptom is often correlated with a lack of accountability within the team.

Focus May Increase Efficiency, But Doesn't Guarantee Better Deals

This article analyses how accelerator focus on a vertical affects the business, and is part two from a series of insights drawn from 50 in-depth interviews taken over the past two years and 126 responses to a survey we sent out recently. To better understand our process and the methodology behind these findings, make sure to read Disciplined Accelerator: Introduction.

Findings

- Today, there is an abundance of options for startups. This makes the competition fierce, so accelerators have to find ways to appeal to top startups. Specialization is the most common strategy to tackle deal flow quantity and quality.

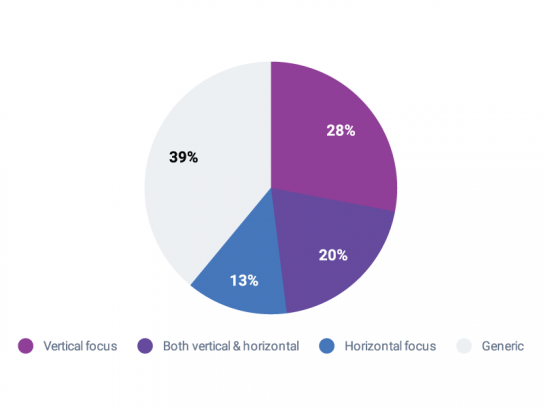

- Focusing vertically (on an industry), horizontally (on one or more disciplines, such as AI, blockchain, FinTech, etc.), or both is a strategic option aiming to improve the efficiency of the accelerator’s programs. Of the accelerators we’ve interviewed, 61% have a focus, 48% having a focus on one or more industries (at least).

- 87% of accelerators with a horizontal/vertical focus reported difficulties in getting enough applications. The narrower the accelerator focus, the fewer the applications. On the other hand, the quality of the applicants is much less of an issue.

Since we focus on specifically mediatech content tech startups the deal flow is very fragmented and it's hard to come by good leads by standard deal flow tools and methods.

— Sten Saluveer, Storytek Accelerator

- Expanding or narrowing focus geographically helps balance the vertical/horizontal focus shortcomings. Roughly ⅓ of our respondents focus locally, another ⅓ focus regionally (across countries/states) and the rest ⅓ try to appeal to a global audience.

Thoughts

- It’s an assumption we will check further, but despite focus being an obvious strategic option for improving the deal flow, we believe that it has an inconsistent influence on deal flow. Focusing decreases the quantity of applications (already an issue) but increases the quality of startups (mostly because of better marketing positioning).

- Choose your focus based on your strategic assets: corporate partnerships, mentor and expert networks, other strong relationships, access to consumers or corporate clients, the availability of talent. Again, ask yourself what you ask your founders: what is our unfair advantage (something that cannot be copied or replicated) and is key to our success?

- Expanding across borders or even globally is a way to increase the number of applicants, but unless you have access to strong international networks (customers and partners), you won’t be able to further support your startups to reach their potential. So it might be more useful to adopt a few good cockroaches, rather than a delusive unicorn.

- Defining your accelerator focus won’t improve your top of the funnel (on the contrary) but it will improve the outcome of your accelerator programs.

Deal Flow Is a Major Challenge for 2/3 of Accelerators

This article is focused on deal flow challenges and is part one from a series of insights drawn from 50 in-depth interviews taken over the past two years and 126 responses to a survey we sent out recently. To better understand our process and the methodology behind these findings, make sure to read Disciplined Accelerator: Introduction.

Findings

- 2 out of 3 accelerators we’ve talked to have deal flow challenges.

- 59% of all accelerators get low-quality applications. 31% don’t get enough applications. 26% of all accelerators get both insufficient and low-quality applications.

- Reasons for these challenges are lack of awareness and reputation (especially for new accelerators), competition (with other accelerators, investors, grants or various startup programs) and unbalanced offering (cash vs. equity).

- Accelerators offering $100,000 or more in funding have fewer deal flow challenges. On the other hand, the ones offering less funding have quality issues (startups don’t perceive the mentoring and support as bringing enough value to justify the amount of equity).

- Marketing budgets are too limited to allow being effective on all fronts (awareness, trust, lead generation, qualified staff).

- Applications coming in as a result of marketing campaigns are of much lower quality than the ones coming in from mentor/partner recommendations.

Over 70% of our deals come from introductions from our mentors or overall network, not by marketing efforts.

— Les Schmidt, BRIIA

Thoughts on deal flow challenges

- Ongoing scouting: Getting better applicants starts long before promoting your new program. The advice you give to your startups to GOOB (get out of the building) applies to you too. Conferences, meetups and other events are a good place to connect to good startups. Be proactive about it and set metrics for your team. The good old days when startups applications flooded every accelerator program are gone. Competition is fierce for top startups. Even though you’re part of those lucky 33% accelerators without deal flow problems, scouting can only increase the quality of your deals and the size of your network.

- Build a stronger network: Many accelerators don’t have the YC luxury of getting more applications than you can handle. In many situations (one example is Thailand’s ecosystem, driven by corporate accelerators), the number of applicants is often too small to get a decent quality across your cohort. Therefore, recruiting through referrals and recommendations is a much better source for quality, vetted deals.

Going to events not only for networking but to give back is important. All startup communities are local, so you have to give back to the community—this is why, for us, 80% of the deals came through recommendations.

— Cosmin Ochișor, former Hub:raum Krakow WARP, now partner at Gapminder. - Involve your network in the deal flow: Mentors are some of the best deal sources. Involving them in generating deal flow (beyond sending an email begging for them to share your marketing page) and in judging/vetting will bring a lot more value in the process—often much higher than what your small team can handle.

- Go beyond Google forms and emails: Use a CRM to handle the deal flow. Of course, we would recommend Metabeta, our portfolio & deal flow suite, but Hubspot, F6S, and Gust are also good alternatives to generic forms. They allow you to involve external judges and have all the information available in one place for your team.