Some of the biggest players in the game, the unicorns that made it on every startups’ “when I grow up” list, are companies that have achieved success by creating platforms which ease transactions between two different sides. Amazon, Airbnb, eBay, Craigslist and Uber are a few examples of marketplaces that became giants in the industry. In Asia, marketplaces are some of the fastest-growing startups.

Typically, marketplaces can be very powerful in terms of growth. But tracking them and measuring their success isn’t always simple. Marketplaces need to address both the supply and the demand side of a business—two types of customers that need different kinds of hooks. Which is double the trouble.

The spectrum of markets in which these types of businesses activate is wide, which is why each calculation should be tailored to the specifics of their market focus, whether it’s horizontal or vertical, B2B or B2C, global or local and so on. But how do you know if a marketplace startup is on its path to becoming huge?

Here is a rundown of the key metrics that any accelerator or investor should look for when dealing with marketplace startups:

Gross Merchandise Value (GMV)

The GMV shows the total of the goods and services transacted within the business. You can calculate it multiplying the number of transactions with the average order value over an extended period of time (usually done yearly).

GMV = Number of transactions × Average Order Value (AOV)

Some consider this metric to be a vanity metric. And the reasons are twofold:

- discounts, cash-backs, returns, and cancellation are not included in the equation.

- GMV is an indicator of the volume of money transacted within the platform, but not how much money it actually makes (i.e. revenue).

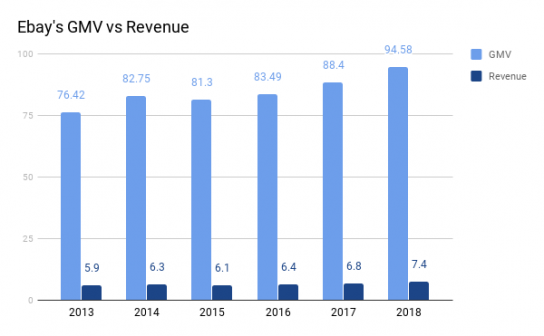

For example, eBay’s GMV amounted to $95 billion in 2018. That looks impressive. But when you look at its net revenue, the company made only $8 billion through its marketplace transactions. While still a lot of money, the difference is sizeable.

Another example would be Etsy, which reported in 2018 Q3 a GMV of $923 million and its revenue of $111 million.

Achieving a high GMV means either:

- having a high number of transactions but with low AOV,

- or a low number of transactions but with very high AOV.

Experts don’t agree on which of the two is the better one in terms of strategy. It takes looking at other metrics, such as the customer acquisition cost (CAC) to be able to assess the real monetary value of the platform. But ultimately, a growing trend line in the GMV value shows how popular that marketplace is becoming, how well it is performing, and if it is worth investing in it. In a seed to Series A type of startup, the growth seen should be 100% annually.

If the startup is at its early-stage it will not have a lot of GMV growth to measure. In that case, it is helpful to look at companies with similar business models and pricing strategies to see when their growth spur occurred. Understanding more about what others have done in the past, and at which point in their business life the boom happened, will make it easier to conclude if the startup is heading in the same direction.

Rake (Take Rate)

The revenue of a marketplace company is the total amount of commissions and fees applied to the transactions within the platform. You’ve probably heard it mentioned as the “take rate”.

Rake = (Commission + fees) / Sales

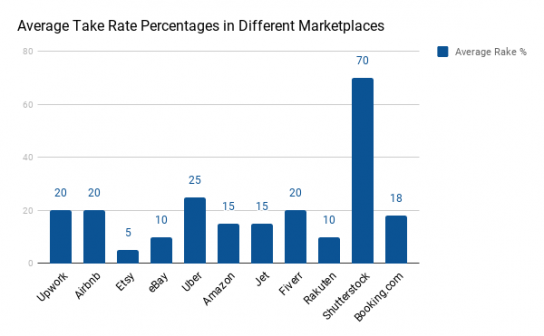

Much like regular pricing models, these rates come in various shapes and sizes. Founders can choose to apply this rate either to the demand or the supply side (sometimes both), it can come as a fixed or flexible commission, a flat fee or a percentage, it can even be subscription-based. The value of this rate varies based on the type of good that is being transacted and the business model of the marketplace. On average, it is somewhere between 5–30%.

Upwork uses a regressive take rate model, charging less when billing more, scaling down from 20% to 5%. They apply this fee only to the freelancer, so it is one-sided.

Airbnb has a double-sided commission. While the percentage for hosts stays put at a 3% fee, the service fee for guests fluctuates around 20%. And as the cost of booking increases, that percentage decreases.

Etsy does not have only one type of fee. They have standard fees that apply to all sellers (which is a 5% take rate on each transaction, or a US$0.02 fixed fee for each item listed), fees that are optional based on extra services they provide (such as a tool for creating personalized websites) or a subscription-based fee.

Each startup has to choose their own rate model based on the specifics of their market. That rate does not have to stay the same, anyone can adjust it as they see fit. Price increases are not pretty but sometimes necessary and if done correctly, the way Etsy did, they come with benefits. After years of growing their user base and gaining their trust, they went from a 3.5% to 5% rate and added their subscription-based plans. That resulted in a 43% revenue increase (comparing 2017 Q3 to 2018 Q3).

Early stage startups can (and should) opt for lower rates, for the sake of cash flow but also to be able to enter the market and compete with the giants. Once they scale and reach exponential growth, marketplaces tend to take up most of the space leaving little room for competition. A good example of a new player that disrupted an industry that seemed untappable is Booking.com. They conquered the European market by providing smaller fees that smaller hotels could afford. That increased their supply, which met the already high demand. And later on, they compensated for the small fee by adding optional promotional features that hotels were willing to pay.

Liquidity

Which leads us to one very important aspect of why choosing the right take rate matters: liquidity. Appealing rake models bring in users which in turn affects the increase of the GMV. And ultimately makes for a steady revenue stream—which is the interconnectedness of things.

Liquidity in a marketplace is the balance between the demand and the supply sides of the business. Having enough buyers and sellers, or a good ratio between them (or items sold/booked) is essential for a marketplace to grow.

Etsy had around 34 million active buyers and around 2 million active sellers, in Q3 2018, which does not seem like a good ratio. Measuring liquidity, in this case, means looking at more than the number of buyers and sellers, so other aspects factor in the equation:

- number of listed items that each seller has;

- variety of products;

- number of purchases;

- return purchases;

- geographic distribution (shipping destinations vs website traffic);

- other things that are particular to the marketplace.

Service-oriented marketplaces vs product oriented ones should have their liquidity measured by different standards, or within different timeframes. A working contract on Upwork could take months before it ends while buying a photo on Shutterstock only takes a second. The same goes for global vs local marketplaces. Deliveroo needs both the buyers and the sellers to be in the same code area to reach liquidity, while Bookdepository ships worldwide and the same rule doesn’t apply to them.

This chicken-and-egg conundrum proves that in a marketplace the number of buyers and sellers is co-dependent, that having one without the other is pointless, and on which of the two a founder should place their primary focus is unknown. With competition being so intense, it’s critical for each marketplace to have liquidity. The business needs to have a strong value proposition and provide a great user experience, in order to gain the trust of both sides. Not having enough (in terms of quantity but also quality and variety) supply is dangerous, as anyone looking for anything can quickly find it elsewhere. It goes without saying that a marketplace without an increasing demand points to a dead end, or that a market-product fit doesn’t exist.

Ending thoughts

Marketplaces are growing strong and investing in them is wise. These three key metrics show without a doubt the company’s performance, viability, and growth. There are many other metrics that you should take into account for a full evaluation. But at an overall level, Gross Merchandise Value, Rake and Liquidity are the three musketeers that tell you everything you need to know about the health of the marketplace startup.

To go more in-depth, these articles provide a good deal of details and more metrics:

How to measure your success: The key marketplace metrics (Sharetribe) looks further at usage metrics, customer conversion funnels and user satisfaction metrics.

Marketplace Liquidity (TechCrunch) tackles the importance of liquidity in a marketplace at a more granular level.

A Rake too Far: Optimal Platform Pricing Strategy (Above the Crowd) although written a while ago, Bill Gurley’s thoughts are still applicable to today’s marketplaces.

Diana Niculae Grigorescu

Super awesome marketing girl claiming she is more chaotic than she really is.